Again and again, brand and audience research manages to provide “information”, but little to no insight. Even more rarely it actually inspires to make useful adjustments.

How come research still so often misses its point? And how do you put quality above quantity?

Advertising guru David Ogilvy already noted in the 60s:

“I notice increasing reluctance on the part of marketing executives to use judgment; they are coming to rely too much on research, and they use it as a drunkard uses a lamp post: for support, rather than for illumination.”

Fast forward 50 years and you’ll notice that little has changed. The way in which research results are used sometimes is questionable. On top of that: How things are being measured is often reason enough to make you squirm.

As a result, many research investments provide “information” but very little useful market insights in the world of the customers, let alone inspire the right follow-up (like smart product or service adjustments, policy, marketing or communication strategy).

Don’t tell your boss what he wants to hear

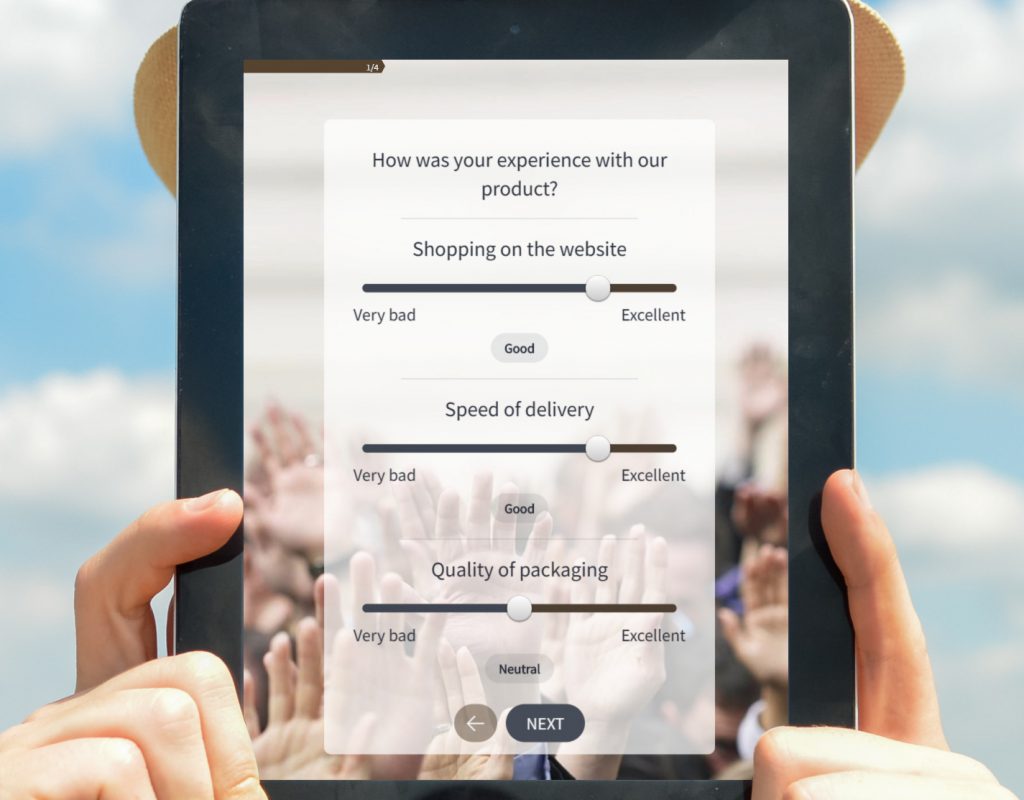

Consumers/citizens get an astonishing amount of nonsensical market research surveys a year. The alarming truth is that even renowned market research agencies and institutions are guilty of this.

When setting up research one simple rule applies: Garbage in, garbage out. And trust me, there’s a lot of garbage out there.

I live in the Netherlands, and recently I was asked to “give my opinion on the neighborhood”. Like most residents, I was excited. What surprised me: the most notorious problems (marine litter, congestion, Airbnb) were not even mentioned.

However, what I could state my opinion on was whether I’d like to talk to a home coach (?), if I know the phenomenon “neighborhood restaurant” and on which days I can take out the garbage. I had very little room to voice my opinion, which is what audience insights are all about.

What you don’t ask, you don’t hear

The marketing research process of the Municipality Amsterdam is similar to a doctor who asks his patient with pneumonia whether her feet hurt. When she says no he concludes “There is no need to worry, you are perfectly fine”. What you don’t ask, you don’t hear.

The most hilarious part was a participation in the research survey wasn’t limited to the residents. Anyone who knew the postal code could participate. Even parties who benefited from an ‘Everything’s fine, most residents are already super happy’-conclusion (like the notorious beer-bike operators).

Do you want to know what your customers deem important, or do you want to confirm your self-image?

The same story unfolded this past weekend. I got a questionnaire regarding my most favorite theater festival. Even to me, a hardcore-fan, the questions (like 20 reputation related questions about the “festival as a whole” proved to be a challenge.

I was asked if I found an aspect such as “marveling”, “excessive” and “touching” apply to the festival as a whole. Well, despite my love for the festival I never even thought about the listed “aspects”. Much less they had any influence on my visit to, and love for the festival.

What does it matter whether visitors find the festival “excessive” or not? (what do they even mean by this?) And what use is it to the festival knowing I find their reputation “celebratory”?

More interesting marketing research questions would be:

- How important do you deem the reputation of a festival?

- How would you describe the festival’s atmosphere?

- What gives it this celebratory atmosphere?

- Why does this feel more/less celebratory than other festivals?

- What could the organization change to enhance this feeling?

But that, of course, was never asked. I truly wonder what the organization gained from this research. To me, it mostly seems like subsidies which were thrown out of the window.

14 statements about an abrasive pad brand, seriously?

Sadly the example of the festival-questionnaire isn’t the only one of its kind. This “active knowledge” customers have of products, brands, organizations and subjects is often severely overestimated.

Let’s face it: the heads of consumers are bursting with information.

Even if they save some information about a brand, this mostly consists of nothing more than a couple key words, a few images, a feeling.

At the same time, marketers and research agencies do not back down to give a respondent 20 to 30 statements about far-fetched reputations and personality traits. Well, when you ask someone a question, they’ll answer, even if it’s about something they have absolutely no opinion about.

But what does this tell you about their active experience with you? Barely anything.

Measure the change you’d like to see

What good is an opinion if you don’t know what’s behind it?

Another problem of gaining market insights is the questions aren’t straight forward enough.

What can you answer to statements along the lines of “This product is completely contemporary”. or : “This is a product which suits me”. And even if I’d answer “yes”, what market insights do you actually get?

Fair enough, you know to what extent customers consider your product replaceable or special. But the question remains whether the answer actually helped you to figure this out: “Do you agree brand X is unique?” if 80% answers yes to this, what do you actually know?

It only gets interesting at the “Why?”

Research, “just because you can” or…

And, to be honest: do these yearly expenditures really justify their means? Do these help you to make decisions?

Do you conduct a yearly evaluation because it grants you brand insights into your policy, marketing and communication strategy, or because you’ve been doing it for years?

What use is it to measure your reputation using generic characteristics? A couple of thousand euros a year to be part of an industry monitor may sound like a bargain, but if it doesn’t provide you with anything useful, it’s a rather foolish investment.

How much certainty do numbers really give?

Information without insight grants you absolutely nothing

In short, quality beats quantity. Go big or go home.

- Only use the most important questions. Start with a clear goal: what do you want to know? Why are the answers to these questions important? What future decisions does the research have to support?

- Don’t be fooled by numbers. Qualitative scores by themselves are not enough, you have to know what’s underneath.

- If you use a quantitative research method, do it in a qualitative way. It’s better to operationalize 1 or 3 components of your reputation, than 20 who are just “meh”.

- Stop throwing money at industry monitors because you’ve been doing it for years.

To what extent do you see chances to optimize your marketing research process? I’m curious.